The Żejtun Roman Villa

Wirt iż-Żejtun welcomes you to this website dedicated totally to the Żejtun Roman Villa. Our aim is to create awareness of and to share information about this important archaeological site located within the town of Żejtun in Southeast Malta, the name which it got from the olive itself.

The main source of the information being shared on this platform is the publication “The Żejtun Roman Villa: Research, Conservation, Management” which was published by Wirt iż-Żejtun following a symposium held in 2012. The publication includes twelve papers which were presented by researchers and academics.

A virtual reconstruction of the Żejtun Roman Villa is being presented on this platform. This virtual model together with an animated video describing the olive pressing process during Roman times were produced by Wirt iż-Żejtun with the direct assistance and contribution of a number of academics from the Department of Classics and Archaeology at the University of Malta and the Senior Curator of Punic, Roman and Early Medieval sites at Heritage Malta. These productions were co-financed by the European Union through the LEADER project managed by the Gal Xlokk Foundation.

Location

The remains of the Żejtun Roman Villa lie on the highest point of a long, somewhat flat ridge that stretches for about 1 km roughly in an east-west direction. This point is located close to the east end of the ridge. Beyond Triq Dun Lawrenz Degabriele that borders the Zejtun Secondary School grounds on the east side, this ridge starts dipping rather rapidly towards Tas-Silġ and Delimara, along the road leading to those destinations. The ridge dips slightly less rapidly to the north, beyond Triq Luqa Briffa, even less rapidly to the south, beyond the Żejtun Bypass (Triq il-President Anton Buttigieg) while it maintains more or less the same altitude to the west up to Bir id-Deheb from where the ground starts rising again towards Gudja and the parish church of Ħal Għaxaq.

The ground level of the Villa remains is approximately 60m above sea level, a few metres higher than that of the old parish church of Santa Katerina (the present St Gregory’s church) and considerably higher than that of the present Żejtun parish church.

The discovery

Everyone who used to live close-by, and was familiar with the area later occupied by the school states that no signs of the presence of ancient remains were apparent in these fields before 1961, when “traces of masonry and some pottery came to light” during soil clearance works for the building of a new school for the village.

The Museums Department was then called in to investigate but the remains were deemed to be “slight” and no further action was taken.

Excavations

The Museums Department was notified of the appearance of more remains in 1964, which they identified as belonging to a “Punico-Roman building”.

Investigations were conducted, by Francis S. Mallia at intervals between April and July and three distinct features were identified and surveyed: a large cistern; a line of stone water-channels; and a foundation wall separated from a nearby stone-paved area. But no connection between the three features was discerned.

Interest in the site was revived

in 1972 when a full-scale excavation, using volunteer assistance of Maltese and Italian students assigned to the task by the Minister of Education and Labour, appears to have cleared the section with the olive-oil pressing apparatus.

After 1972, excavation campaigns were regularly reported on in the Museum Annual Report up to 1977. Meanwhile, it seems that the excavation of the site was assigned to Tancred Gouder,

the newly appointed Assistant Curator of Archaeology.

In 2006 the Department of Classics and Archaeology of the University of Malta embarked on a research excavation project at the Żejtun Roman Villa. The last campaign was held in 2018. The archaeological investigations were intended to assess and record the remains uncovered in 1964 and in the 1970s and other data arising from new excavations at the site. In addition, the fieldwork provides undergraduate students reading for a degree in Archaeology at the University of Malta with the practical skills related specifically to excavation, including on-site recording.

Some preliminary observations

by Anthony Bonanno

On 22 July 1975, after having visited the site, I jotted down some observations in an ‘exercise book’ with a blue cover (copies in file entitled “Żejtun Roman Villa Excavations” in the archive of the Department of Classics and Archaeology of the University of Malta). The following is an annotated and interpreted summary of those observations:-

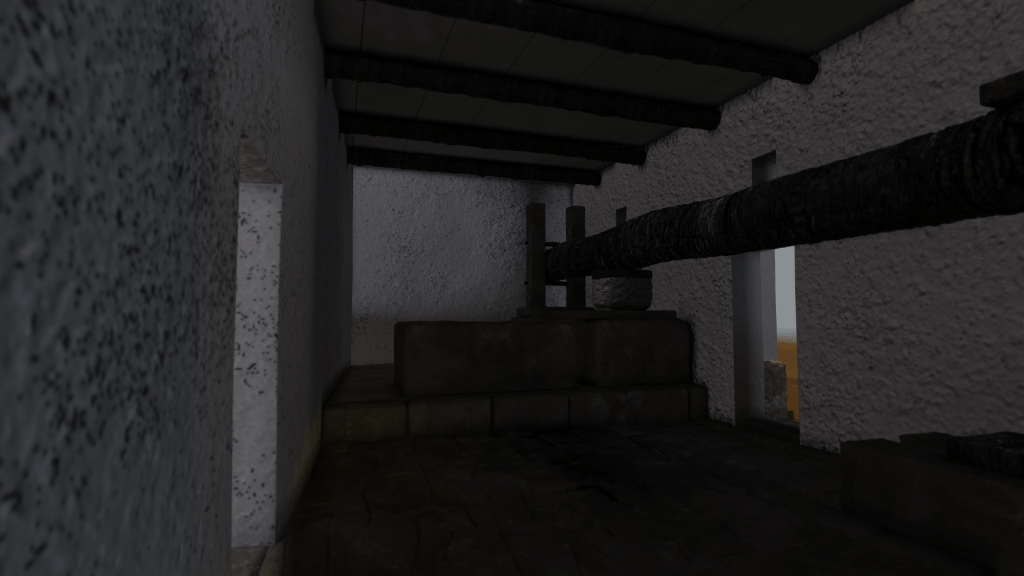

The site was clearly a domestic country settlement with a section intended for residence and many heavy stone elements indicating a working area for olive pressing, such as a huge parallelepiped block pierced by various holes and channels intended to support a massive wooden frame which in turn held in place the prelum (a horizontal beam that would have exerted pressure on the olive mash contained in an ad hoc wicker container). Similar anchor blocks have been encountered in other Roman villa sites in Malta – as well as abroad – such as the one of San Pawl Milqi. A square block hollowed out to form a circular liquid container has parallels in a row of three such vats discovered in the same olive pressing complex of San Pawl Milqi. It is more than likely, therefore, that like them it served the purpose of olive oil decantation. What was missing in the Żejtun complex was the press bed, a flat block with a circular groove to direct the pressed oil towards the decantation vats, a good example of which survived at San Pawl Milqi. A broken part of a rectangular stone platform with a slightly raised border and two circular depressions in the centre was thought at that time to be such a press bed.

On the other hand, the residential area immediately to the south of this industrial complex consisted of at least three rectangular rooms, one of which could be described as a long hall, all paved with lozenge-shaped tiles.

The laying of differently coloured tiles here formed a herring-bone pattern, unlike the cascading cubes pattern produced by similarly shaped terracotta tiles in one room of the Roman villa discovered at L-Iklin in 1975 and by marble tiles at the Roman domus in Rabat.

These rooms were enclosed by walls that were plastered and decorated with simple line paintings in red, yellow and green, traces of which survived. In the north squarish room to the east of the large tiled room I had noticed that some traces of painted plaster were covered over by another layer of plaster. Near the east corner of the south wall dark red vertical parallel lines were observed, as well as possibly curved yellow traits to their right. Towards the centre, I could see two thicker, dark red, vertical lines, a dark blue line curving down to the left and beyond it, to the left, a large area painted in light green. To the right was yet another very thick, vertical dark red line. Several parts of this painted surface were covered by a layer of plaster. More dark red, vertical lines were seen on the left of the south wall, while closer to the left corner further traces of light green areas, dark green lines and small yellow patches could still be seen. I interpreted these as imitation marble inside panels. I also saw other traces of colour on the north wall where it was clear that the painted plaster belonged to the same period as the tiled floor. I ended my observations by suggesting that samples of the plaster should be extracted for chemical analysis.

On the basis of this type of wall painting (ad incrostazione marmorea, that is, in imitation marble) and similarities to the wall paintings found at San Pawl Milqi, I believed that the first Roman structure might have dated to the 1st century AD, though I reserved judgement for

after an analysis of the associated ceramic material. Since Tancred Gouder (verbal communication) dated the villa complex to the 3rd-4th centuries AD on the basis of the ceramic material found in the previous excavation campaigns (which I had not seen) and of a small coin hoard he had discovered in one of the rooms (retraced in Malta Central Bank deposit), I assumed that the villa could have been built in early imperial times and was reused, or continued to be in use in late Roman times. Evidence for this re-use came not only from the layer of plaster mentioned above, but also from a number of architectural elements that were not found in their original context, like the plain base of an engaged column, a four-sided plinth topped by a moulding, and various other ashlar blocks which did not fit in the original construction pattern.

Another observation that I made in 1975 regarded the elevation of the walls of the tiled rooms. I came to the conclusion that in one or another of the building stages, the walls consisted of regular ashlar blocks only up to the height of the first course above the floor, the rest above that being constructed of mud brick. I had come across such a technique during my participation in the excavation of a section of ancient Berenice in Benghazi in 1972 and 1973. In one area a whole section of a collapsed mud brick wall, about 2 x 1.5 m, was discovered in perfect condition lying on its side. In Żejtun a few traces of disintegrated mud bricks could be noted at that time in the east wall of the same painted and tiled room mentioned above, behind a projecting section of the painted plaster which was not supported by a stone wall. Since crudely fired bricks had also been found on the site, it appeared that this building technique was also in use.

An important discovery

It was in the summer of 1976 that Prof Anthony Bonanno directed two one-week campaigns, one in July (5-11) and one in September (3-14) 1976, in connection with two Summer Schools in Archaeology organized by the National Student Travel Service (NSTS), Malta. Again the physical work was done by students, foreign and local, but they had attended a theoretical course in archaeology. Following the excavations, a report was submitted to Tancred Gouder, the Curator of Archaeology, recording these two summer excavation campaigns.

Perhaps the most important find from this excavation was that of two fragments of a cooking pot, one of which carried an inscription in Punic characters which, by comparison with others found at Tas-Silġ, was read as a dedication to Ashtart. The same reading was confirmed first by Tancred Gouder and, eventually, by Benedetto Rocco who was on a short visit to the island. A further, more in-depth study of the inscription, proposed the identification of another possible female divinity, namely Anat, instead of, or in addition to, Ashtart.

Photograph: Department of Classics and Archaeology, University of Malta, 2012.

The University of Malta Excavation Project

by Nicholas C. Vella

In 2006 the Department of Classics and Archaeology of the University of Malta embarked on a research excavation project at the Żejtun Roman Villa following requests from successive school heads and the Żejtun Local Council. The archaeological investigations were intended to assess and record the remains uncovered in 1964 and in the 1970s and other data arising from new excavations at the site. In agreement with the Superintendence for Cultural Heritage, five areas were chosen for investigation. Areas were aligned along a 10 x 10 m grid laid out on site by a team of surveyors from the Malta Environment and Planning Authority who also set up a site benchmark (63.51 m above mean sea level). To date, short excavation campaigns have been held each year between 2006 and 2009 and again in 2011 and in 2012 under the co-directorship of Prof. Anthony Bonanno and Prof. Nicholas Vella. Further site excavations were carried out up to 2018.

The method of excavation used in the project is a stratigraphic one, where each unit of stratification (termed a Stratigraphic Unit) is identified and recorded as part of a stratigraphic sequence. The methods of digging and recording follow those that have been used by the Department on other projects, namely at Tas-Silġ and at Għar ix-Xiħ on Gozo, and are in line with the requirements of the Superintendence for Cultural Heritage. A site code – ZTN06 – was designated by this office for use throughout the duration of the project for all recording purposes.

In all areas investigated particular attention was given to defining the extent of past interventions, both horizontally (defining the limits of the rectangular trenches) and vertically (determining the depth of previous interventions). Careful, stratigraphic excavations are allowing the team from the University of Malta to piece together the complex history of what is clearly a multi-period site. That this is so was already apparent in the 1970s and is confirmed from the recent study of the pottery recovered in the 1972 excavation season.

The investigations revealed the extent of the room where the beam-anchoring device (or anchor block, measuring 3.6 x 1.56 x 0.76 m) is situated, uncovered the large 1.56 x 0.92 m slab with shallow cup-like depressions (diam. 0.20 m) that had been identified in the 1970s, and excavated one baulk which was found to contain a number of fired bricks and small fragments of worked marble. An important discovery was made in the area contiguous to the stone vat, presumably meant for the decantation of olive oil, where excavations below the “working area” of Mallia’s 1972 sketch plan revealed a large damaged stone slab (2.20 x 1.10 m) with another cup-like depression; it had clearly gone out of use when it was covered over. The function of these slabs with cup-like depressions does not find parallels in the standard literature on Mediterranean olive-pressing installations from antiquity. At the San Pawl Milqi villa site, however, similar floor slabs (one with a cup-like depression) are known, one adjacent to the other and surrounded on three sides by slabs of stone placed vertically and covered, in part, by successive layers of hydraulic mortar. They have been associated by Locatelli with the remains of tanks used for the collection of oil in Period VI of the villa’s history, dated to the second quarter of the 3rd century AD and the beginning of the 4th century AD. A similar function for our slabs is certainly possible; indeed, the large slabs identified in Mallia’s sketch plan with a “working area” could have been used to line the tank on its four sides.

The present work will allow us to unravel the story in as much detail as possible and begin to understand the site in the context of other archaeological sites in this part of Malta.

Further information on these excavations can be found in the paper “The Żejtun Roman Villa: Past and present excavations of a multi-period site” written by Prof. Anthony Bonanno and Prof. Nicholas C. Vella, included in the publication “The Żejtun Roman Villa: Research, Conservation, Management”.

The Villa

The layout of the villa was reconstructed from the ACAD drawing produced by Dario Nigro, and edited by Dr. Maxine Anastasi in 2014 and under the direction of Dr. Ing. John C. Betts, Head, Dept. of Classics and Archaeology; Prof. Anthony Bonanno; Prof. Nicholas Vella; and Dr. Maxine Anastasi.

This virtual reconstruction was possible through a continuous consultation process with Dr. Maxine Anastasi and David Cardona, the Senior Curator for Punic, Roman and Early Medieval Sites at Heritage Malta.

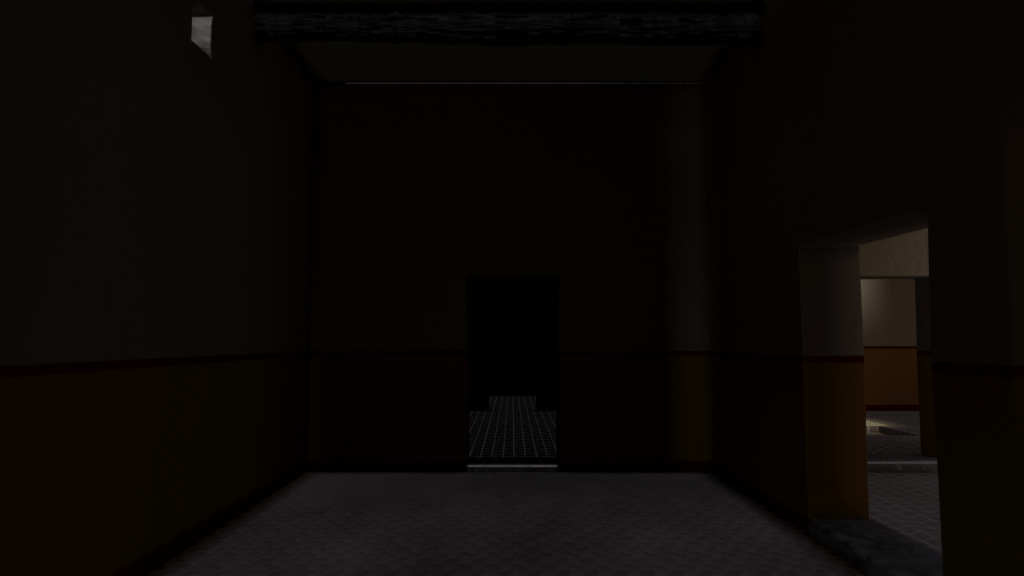

The presumed main entrance of the villa (1) faces west and leads to the atrium (2). In the classic layout of the Roman domus, the atrium served as the focus of the entire house plan. As the main room in the public part of the house, the atrium was the centre of the house’s social and political life. The atrium used to have a central skylight (compluvium), and in the middle of the atrium was the impluvium, a shallow pool sunken into the floor to catch rainwater from the roof.

The peristyle (peristylium) (3) was the main open courtyard within the villa. It was surrounded by a corridor possibly having a terracotta tiled roof slanting inwards and supported by a series of columns. A well or cistern, with a cylindrical well-head is usually found in the middle of the courtyard. Although the location of the peristyle in the Żejtun Roman Villa has been identified, no architectural remains were found which could help archaeologists determine the architectural detailing of this important space within the villa. Therefore the reconstructed peristyle in our virtual model is inspired by the evidence from the Roman Domus in Mdina.

The living and private areas of the villa are made up of a number of rooms surrounding the peristyle. These rooms are typically dark since the only source of natural light was usually gained from small high-level windows located in the facades and larger windows overlooking the corridor in the peristyle. At the Żejtun Roman Villa, some of the rooms in the living area (4) have lozange pattern terracotta tiles, while in room 5, square tiles appear to have been used. The residential part of a Roman villa usually includes a tablinum – the office or living room for the man of the house; a triclinium – the dining room; a cubiculum – the bedroom; and a culina – the kitchen.

The industrial area at the Żejtun Roman Villa is located in its northern half and can be easily identified through the olive pressing equipment found in this area. This is the most faithfully reconstructed part of the Żejtun Roman Villa model, and is based on discoveries made here and at other villa sites in malta and Gozo.

The open courtyard (6) in this area includes a cistern and probably was the area in which the olives were brought soon after being harvested. Within this area, the archaeologists discovered the stone water conduits, which were possibly used to channel the rain water from the roof into the cistern. This courtyard and the rest of the industrial area was paved with large and irregular slabs.

Documentary

This documentary was produced in 2012 and formed an integral part of the exhibition about the Żejtun Roman Villa, curated by Wirt iż-Żejtun, during the Żejt iż-Żejtun folklore festival held in September of the same year.

The production gives an overview of the geographical, topographical and cultural setting of the villa. The link between land and sea is an integral part of this setting. The video documents and describes a number of archaeological sites which have been discovered in Southeast Malta, in order to give a historical context to the Żejtun Roman Villa.

The documentary includes an interview with two key academics and archaeologists who studied this site, from the Department of Classics and Archaeology of the University of Malta, namely Prof Anthony Bonanno and Prof Nicholas Vella.

Multimedia

3D Virtual Model

The 3D virtual reconstruction of the Żejtun Roman Villa, was only possible following the archaeological excavations carried out by the Department of Classics and Archaeology of the University of Malta as part of the undergraduate field studies, and the research and studies carried out by the academics within the same department. Direct input during its production stage was given by Dr Maxine Anastasi and David Cardona, Senior Curator for Punic, Roman and Early Medieval Sites at Heritage Malta.

The model depicts the villa as it presumably was in the 3rd and 4th century AD. The reconstruction was mainly based on what was found through archaeological excavations, however some extrapolations and suppositions based on other archaeological sites from the same period, found in Malta and the Mediterranean region, were done in order to complete the model. A decision was taken not to include furniture within the villa, since no tangible evidence on this was ever found.

Olive Pressing Animation

Animations are liked not only by the young ones, but are also interesting to adults. This animation takes the audience to the Roman times and precisely to the Żejtun Roman Villa and its olive groves.

The animation describes the whole process of olive oil production, as it is thought to have taken place during this period and also highlights the social hierarchy which existed. The process starts from the picking up of olives and ends up with the transportation of its main product, the pure olive oil.

It places the Żejtun Roman Villa in what is believed as its geographical and topographical context in the Classical Period.

The animation is in Maltese, however it includes English subtitles.

Credits

Department of Classics and Archaeology, University of Malta for providing researched resources and direct consultation through:

Dr Ing. John C. Betts, Head, Dept. of Classics and Archaeology; Prof Anthony Bonanno; Prof Nicholas Vella; and Dr Maxine Anastasi.

Dario Nigro, who produced the useful ACAD drawing of the excavated site in 2014.

Mannaïg L’Haridon, Alice Sampieri-Feytout, Alexandre Girard – French interns from the Ecole Nationale des Sciences Géographiques (ENSG), who were responsible for the orthophotomosaics.

Heritage Malta for providing the assistance and consultation through:

David Cardona, Senior Curator – Punic, Roman and Early Medieval Sites.

Wirt iż-Żejtun

Perit Ruben Abela, President and Project Leader; Marcelle Cannataci, Proof reading & Translation.

Gal Xlokk Foundation

Dr Philip von Brockdorff, Chairperson; Terence Camilleri, Manager; Madeline Micallef, Secretary.

Planning Authority:

SintegraM data, (2018), Developing Spatial Data Integration for the Maltese Islands, Planning Authority.

Shadeena Entertainment

Martin Bonnici & Perit Bernice Casha.

Studio 7

Amanda Ciappara Mizzi; Annalice Fenech; Anton Camilleri; Fadi Abou Rjeili; Joel Cutajar; Manuel Ciantar; Suzanne Ciantar Ferrito.

Atturi: Leah Dimech u Frans Zahra